Note: I wrote the first version of this essay about five years ago. I update and re-release it every year in celebration of Earth Day. It last appeared in Blue Green and Between in April 2024.

In a scene from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, the heroine inquires of the Cheshire Cat: “Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?” When she tells the Cat she isn’t sure of her destination but just wants to get somewhere, he responds: “Then it doesn’t matter which way you go.” Alice is perplexed by Cat and place and way, all at once. So are we all at some point in our lives.

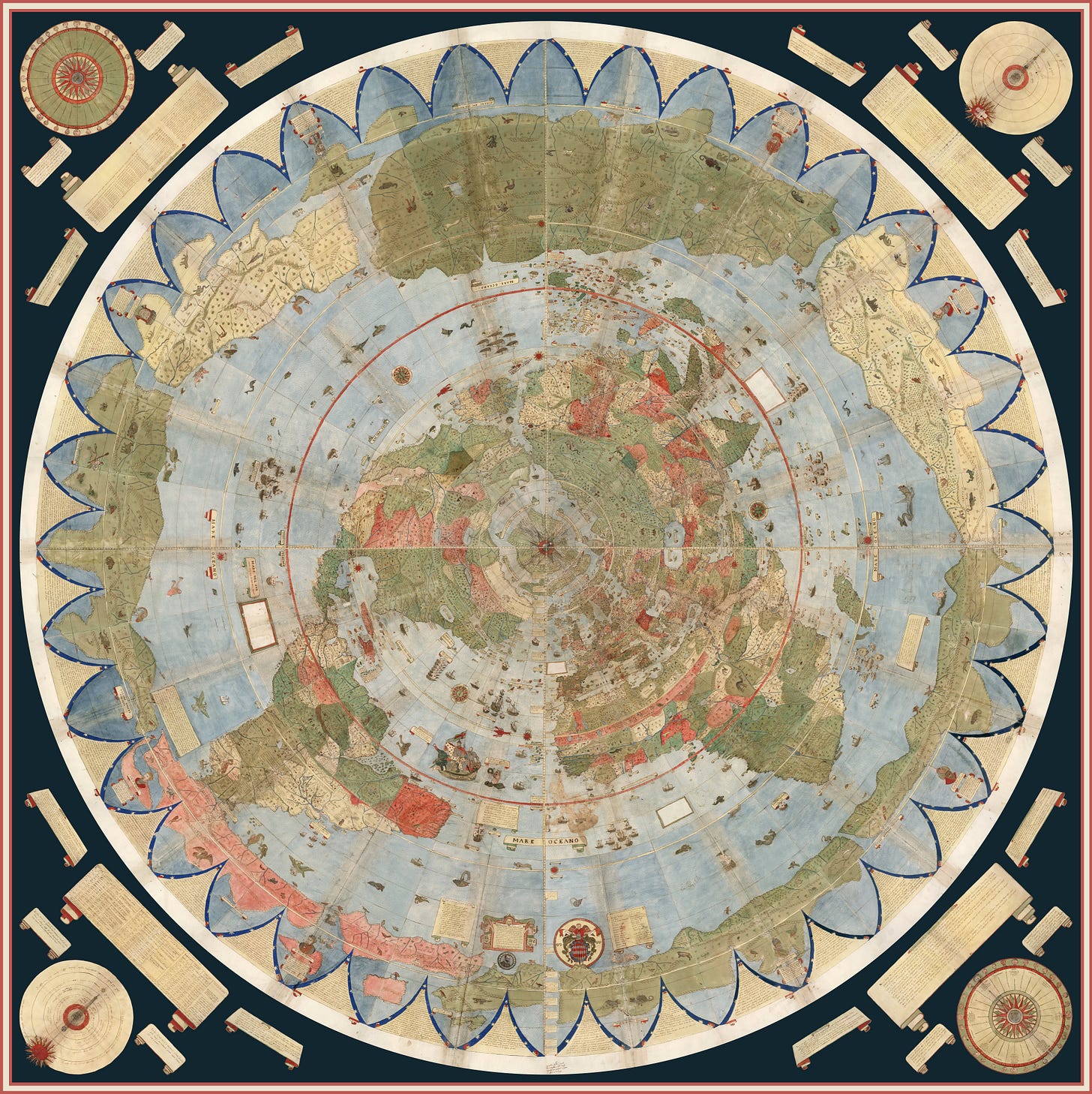

The concept of place has befuddled thinkers and scholars for centuries. Aristotle, in Book IV of his Physics from around 350 BCE, puzzled, “The question is, what is place? presents many difficulties.” Why should place matter? We exist as organic creatures, taking up space, stopping here and there, going to and coming from. But some geography scholars draw a distinction between space (just an area) and place (an important area). Place happens when we attach a value to a specific location: a name, a narrative, our culture, our heart. Then any place becomes some place, a nowhere becomes a somewhere. When we invest value and turn space to place, we care about what happens to it.

Consider. Some of us act like bores in temporary spaces that we aren’t invested in; theater seats, hotel rooms, subway cars, and airplanes are all transitional and transactional space to us. Someone who wouldn’t dream of behaving in a certain way at home—littering, for example—may not think twice about it when they are somewhere they don’t see as their place. But we can’t afford to think that way any longer; the Earth can’t afford it. We must know our place and know that it is bigger than we ever thought before. We face a planet under siege by the combined crises of climate change, disappearing species and habitats, pollution, and out of control consumption. We face a planet under attack by a presidential administration and an unholy alliance of oligarchs who think the planet is theirs to plunder at will for their own power, pleasure, and profit. We must know and love our place, more so than ever before.

We have, from the most ancient times, struggled with this idea of, first, how space came to be, and second, how we transform space to place. One of the ways we’ve always done so is to tell stories about place. In many mythic traditions, the elements of the world—sun and moon, rain and wind, all living things—come into existence by being born from divine parents. In one ancient Philippine creation story, the grandchildren of the gods of water and sky are killed. The grieving grandfathers use the remains of one grandson made of rock to craft the islands of the Philippines, and the remaining three grandchildren made of gold, silver, and copper become the sun, moon, and stars of the world. The primordial frost giant Ymir is chopped up by Norse chief god Odin to provide the seeds for all the parts of the universe; Midgard, home to humanity, is made from his brows. Sometimes a primal human sacrifices their life so that the world might come into existence, Purusha in Indian tales and Pan Ku in Chinese folklore for example. Pan Ku’s breath became the wind, his blood the rivers, and his bones the rocks, among the other elements of the world.

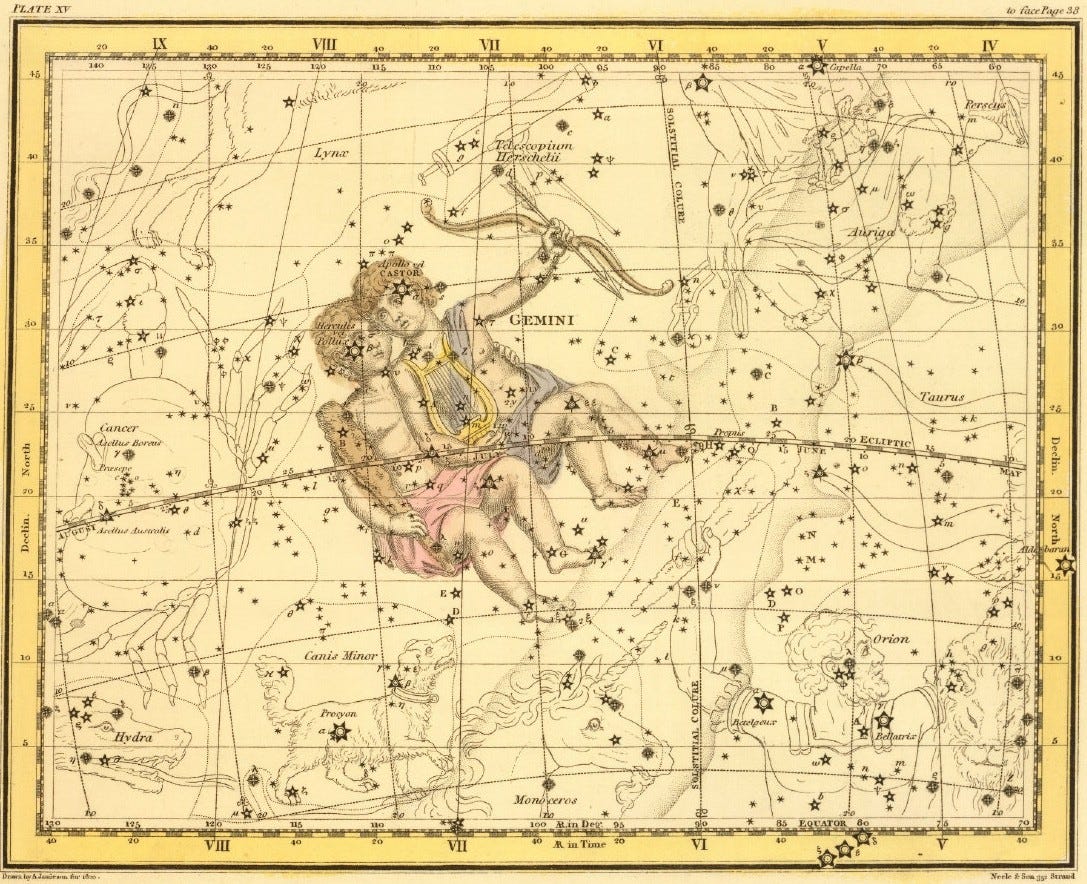

Places tell us their own stories, sometimes in their whys: why is that mountain there, why is that lake here, why the stars glitter, why the sea is salty. The Samoan Islands were made when the creator god Tagaloa needed resting places as he journeyed the world-spanning ocean. In some stories, the ancestors in the Dreaming of Aboriginal people, when they were done creating the world, settled and became features of its landscape. A tale of the Ewe of Africa explains why you see stars at night but not during the day, because the Sun ate her own children, but the moon instead surrounds herself with her children the stars each night.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tesserae to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.