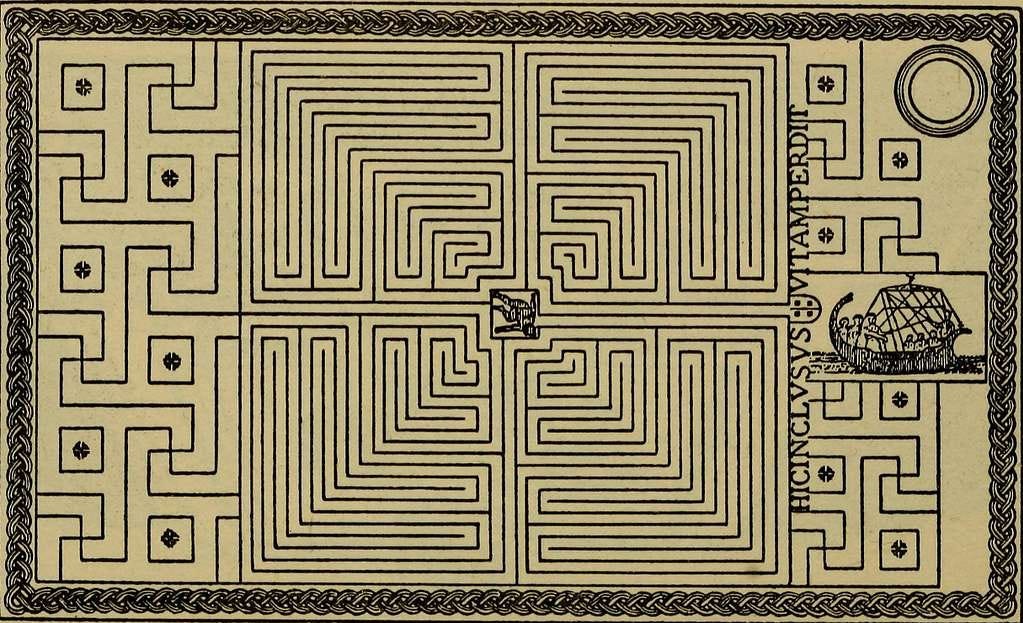

Last October, I won a contest to name a new-to-science deep sea coral. I proposed “golden labyrinth coral,” explaining in my entry:

I chose this name along the same reasoning as ancient Greek historian Herodotus (c.484 – c.424 BCE), one of the earliest scholars to record the existence of a labyrinth, when he wrote: “I found it greater than words can say.” I wanted the name to reflect a greater value than most people place on deep sea corals.

The polyps reminded me of the Greek key symbol seen in so many ancient friezes and of the endless branching and turning of labyrinths. Labyrinths have a sense of mystery, as do deep ocean habitats and beings who survive in a place that is deadly to our species. Labyrinths also have a sense of the holy, the sacred, which we must extend to the wild places and wildlife with which we share our world.

Gold has correlations with great value, with riches and treasures. We also associate gold with a sense of longevity, of perpetuity, for it has been precious to humankind for millennia. So too must we hold our companions on Planet Ocean, be they polyp-ed or plain, scaled or shelled, finned or feathered or furred, barked or stemmed or vined.

The “new-to-science” descriptor is important. There’s nothing really “discovered” about new species; they’ve been hanging around for eons. But we don’t consider them discovered—real—until we give them a name (in this case, Thouarella aureolabyrinthea), vet it with the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, and publish it in a peer-reviewed science journal. The coral I named has been around for thousands, maybe millions of years, minding its own coral business and existing in its coral umwelt. It’s new to us only because we’re newly able to explore such abyssal depths.

The coral of course doesn’t care what we call it. But for humans, naming is a serious, sacred business, perhaps one of the most important we do.

We name things to make them “real,” as in the tradition of some cultures that nothing exists until it is named. In the Bible, after God created animals, He brought them to be named by Adam: “So the man gave names to all the livestock, the birds in the sky and all the wild animals.” Because, in this tradition, they were to be subject to humans? Because God wanted humans to finish the act of creation by realizing our responsibility to them? Because it was a recognition that humans and animals were to be real to each other, sacred companions to each other?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Tesserae to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.